Ivory Coast Chimpanzees crack open nuts and other hard foods with stone tools

NYU Philosophy Professor Peter Unger on Liem’s Paradox: “I like to use this analogy: If you eat Jell-O 360 days out of the year but if you’ve got to eat rocks the other five days, your teeth had better be designed to eat rocks.” (Ref. – Paleomedicina)

Côte d’Ivoire Chimpanzees have been observed in the wild using stone tools to crack open nuts and other hard shell foods. Now a new study suggests that they may have acquired that skill as a result of more gracile dentition, specifically reduction of volume in upper molars.

Côte d’Ivoire Chimpanzees have been observed in the wild using stone tools to crack open nuts and other hard shell foods. Now a new study suggests that they may have acquired that skill as a result of more gracile dentition, specifically reduction of volume in upper molars.

The study was conducted by a group of researchers with the Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Leipzig of course, is the alma mater of recent Nobel Prize winner Svante Paabo. Lead author – Julia Stuhlträger, along with Ottmar Kullmer, Roman Wittig, et.al.

The researchers contrast upper and lower molar strength between the two subspecies, often times referred to as Tai Chimpanzees, and a nearby tribe known as the Liberian Chimpanzees with some surprising results.

Intro summary, research paper, February 21,

Variability in molar crown morphology and cusp wear in two subspecies

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) possess a relatively generalized molar morphology allowing them to access a wide range of foods. Comparisons of crown and cusp morphology among the four subspecies have suggested relatively large intraspecific variability. Here, we compare molar crown traits and cusp wear of two geographically close populations of Western chimpanzees…

Note – instraspecific simply means adaptive traits a species may have for an environment with limited resources.

Characteristics that are often used to define tooth crown morphology across taxa are tooth size, cusp shape, number of cusps or number of enamel ridges connecting the cusps…

Characteristics that are often used to define tooth crown morphology across taxa are tooth size, cusp shape, number of cusps or number of enamel ridges connecting the cusps…

While comparisons of three of the four chimpanzee subspecies (P. t. verus, P. t. troglodytes, and P. t. schweinfurthii) as well as among geographically distant populations of the same subspecies (P. t. verus) have revealed differences in molar (cusp) metrics… little is known about dental morphological variability and tooth use/wear within geographically close populations of a single subspecies. Here, we analyze both the molar crown morphology and the molar cusp wear of two geographically close chimpanzee populations… the Taï National Park in Ivory Coast (Taï chimpanzees) and one from northeastern Liberia (Liberian chimpanzees)…

Note – P.T. Verus simply means Côte d’Ivoire Chimpanzee subspecies.

Evolved tool use may have led to adaptions in molars of Western Chimps

The researchers reference another previous study that found:

The authors found population-specific tooth wear rates depending on the proportion of hard-shelled fruits in the diet; that is, the greatest dental wear was found in the population with the highest consumption rates of the hard-shelled fruits…

The authors found population-specific tooth wear rates depending on the proportion of hard-shelled fruits in the diet; that is, the greatest dental wear was found in the population with the highest consumption rates of the hard-shelled fruits…

The Western chimpanzee population from the Taï National Park in Ivory Coast (Taï chimpanzees) were found to have a less frequent probability of tip-crushing wear facets and no indications of dental chipping compared to [other Chimp populations]. Tip-crushing wear facets and dental chipping are often associated with the consumption of hard food items…

Additionally:

Taï chimpanzees show a significant reduction of the cusp volume, but not of cusp height, on the “single-phase-cusps” of the upper molars with increasing tooth wear…

They go on to note that the Ivory Coast Chimps have a plant-based diet of softer foods, but quite possibly maintain the larger molars for times of stress, when environmental factors cause required dietary changes, such as periods of increased aridity.

Feeding habits “in concordance” with observed tool use

The researchers cite a previous study from 2000, and then note this:

we found for the Taï chimpanzees that “multi-phase-cusps” wear faster than “single-phase-cusps.” These cusp wear patterns are in concordance with the known feeding ecology of the Taï chimpanzees. They regularly feed on nuts/seeds that are opened with tools before consumption… preventing both an accelerated cusp wear and a high occurrence rate of tip-crushing facets… because only the softer endosperm is consumed.

Taï Chimpanzees’ dental morphology mirrors that of 3 million year old Paranthropus boisei

Earlier in February another study was released from the Leakey Foundation that found similar results for another primate species – Paranthropus boisei. Quite ironically, the study was based on two molars found by a research team headed by Leakey Foundation team leader Thomas Plummer at a site called Nyayanga on Lake Victoria, Kenya.

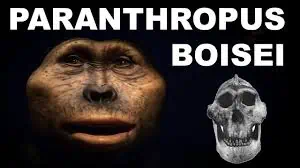

Humans split from our Chimpanzee cousins 5 to 7 million years ago. The first member of our lineage was Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Then came Ardipithecus ramidus and Ardipithecus kadaba (discovered by the Tim White team) 4 to 5 million years ago. After the Ardipithecines the Australopithecines emerged ~3.8 million years ago. They included the star Lucy, Australopithecus afarensis (from Ethiopia), the famous Taung Child, Australopithecus africanus from Africa, but also a side branch including Paranthropus boisei (previsously known as Zinjanthropus) beginning 2.3 million years ago.

From the Smithosinian:

Like other members of the Paranthropus genus, P. boiseiis characterized by a specialized skull with adaptations for heavy chewing. A strong sagittal crest on the midline of the top of the skull anchored the temporalis muscles (large chewing muscles) from the top and side of the braincase to the lower jaw, and thus moved the massive jaw up and down.

Like other members of the Paranthropus genus, P. boiseiis characterized by a specialized skull with adaptations for heavy chewing. A strong sagittal crest on the midline of the top of the skull anchored the temporalis muscles (large chewing muscles) from the top and side of the braincase to the lower jaw, and thus moved the massive jaw up and down.

The force was focused on the large cheek teeth (molars and premolars). Flaring cheekbones gave P. boiseia very wide and dish-shaped face, creating a larger opening for bigger jaw muscles to pass through and support massive cheek teeth four times the size of a modern human’s. This species had even larger cheek teeth than P. robustus, a flatter, bigger-brained skull than P. aethiopicus,and the thickest dental enamel of any known early human.

From the Natural History Museum, London, February 2023, (nhm.ac.uk),

Oldest remains of ancient human relative Paranthropus suggest possible tool use

Hundreds of tools used for cutting, scraping and pounding food were discovered as part of excavations in Nyayanga, a site found on the shore of Lake Victoria in Kenya. Known as Oldowan tools, these artefacts may be up to 400,000 years older than any previously known example

Not only are these tools older than previously known, but also more widespread.

Continuing:

While the manufacture and use of Oldowan technology is generally thought to be associated with early relatives of modern humans, such as Homo habilis and Homo erectus, the discovery of two teeth from Paranthropus, another ancient human relative at the same site suggests potential use by other species.

See our article from Feb. 23, here at Subspecieist, “Louis Leakey vindicated? Breakthrough discovery, Paranthropus boisei

Similar to the Ivory Coast Chimpanzees, another previous study found that Paranthropus boisei had huge molars, but may not have necessarily needed them, except in times of environmentally caused stress.

One study from 2008, by Unger, Grime and Teaford,

Dental Microwear and Diet of the Plio-Pleistocene Hominin Paranthropus boisei

The Plio-Pleistocene hominin Paranthropus boisei had enormous, flat, thickly enameled cheek teeth, a robust cranium and mandible, and inferred massive, powerful chewing muscles. This specialized morphology, which earned P. boisei the nickname “Nutcracker Man”, suggests that this hominin could have consumed very mechanically challenging foods. It has been recently argued, however, that specialized hominin morphology may indicate adaptations for the consumption of occasional fallback foods rather than preferred resources.may’ve been Olduwan tool maker.”

The Plio-Pleistocene hominin Paranthropus boisei had enormous, flat, thickly enameled cheek teeth, a robust cranium and mandible, and inferred massive, powerful chewing muscles. This specialized morphology, which earned P. boisei the nickname “Nutcracker Man”, suggests that this hominin could have consumed very mechanically challenging foods. It has been recently argued, however, that specialized hominin morphology may indicate adaptations for the consumption of occasional fallback foods rather than preferred resources.may’ve been Olduwan tool maker.”

The differences between Paranthropus boisei and P. robustus microwear patterns are more difficult to interpret in this light. Paranthropus robustus has a microwear pattern similar to those of Lophocebus albigena and Cebus apella, two living primates that fall back on hard, brittle foods when less mechanically challenging, preferred resources are unavailable. A hard-object fallback model for P. robustus gains considerable support from recent studies of isotopes, occlusal morphology, living African apes, and plant resources available in the Plio-Pleistocene. If Paranthropus boisei craniodental morphology also reflects fallback exploitation, they likely consumed extremely hard or tough foods even less frequently than did their South African congeners.

Humans split from Chimpanzees 5 to 7 million years ago, and now a subspecies of Chimps shares a morphological and cultural link across the eons with a member of our hominid lineage Paranthropus boisei.

See a related video by our friend History with Kayleigh from 2022, “Stone tools predate ALL human species.” And another video by the Royal Society on Chimpanzee Tool use.

Making this all the more interesting and confusing is a Max Planck Institute study of the long-tailed macaque in Thailand. In its pursuit of harvesting oil palm nuts, it unintentionally produces facsimiles of stone tool artifacts: “complete flakes, fragmented flakes, angular debris, and percussive tools (hammerstones and anvils).”

Findings of the study:

“The macaque flakes overlap substantially with the technological attributes of Oldowan flakes. When a random sample of macaque flakes are incorporated into resampled Oldowan assemblages, a statistical overlap between the original Oldowan and the resampled combined macaque and Oldowan flake assemblage is observed.”

Further, the study concludes that “20 to 30%” of what has traditionally been thought to be “an Oldowan assemblage” hominin tool kit is indistinguishable from what a lower nonhuman primate could accidentally produce in its pursuit of nuts.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ade8159

If the findings hold, the implications are staggering.

It means that not only are we uncertain which archaic hominin has produced Olduwan tools, we don’t even know if they were produced by hominins at all. Nor can we be sure how they were produced and for what purpose. . . .

You are absolutely correct Duncan. I thought the same thing on the Macaques.

Discoveries and findings in paleoanthropology that used to take a decade are now happening every few weeks. Ignorant ideas and dogma are melting faster than Gwyneth Paltrow’s face.

It all leaves this here geezer breathless.