Neanderthal DNA extraction from cave sediments

Anthropologists, Geneticists and Paleontologists have long complained about the inability to extract ancient DNA from hominid fossils in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa. Now, thanks to the Max Planck Institute there’s a new process. And it came about from researching two of the most well-known of all Neanderthal skulls from Gibraltar.

It’s known as the Forbes Quarry Skull, and it was the very first Neanderthal skull ever discovered. The discovery preceded the “Neander Valley” skull by a full 8 years. (Which begs the question, should Neanderthals actually be called Forbes-Quarry-als?)

It’s known as the Forbes Quarry Skull, and it was the very first Neanderthal skull ever discovered. The discovery preceded the “Neander Valley” skull by a full 8 years. (Which begs the question, should Neanderthals actually be called Forbes-Quarry-als?)

The research team at Max Planck used a new method for DNA extraction.

From the National History Museum (hat tip Leakey Foundation), July 15:

Studying ancient human remains can be difficult because they are easily contaminated by modern human DNA.

To investigate DNA preservation in these Neanderthal remains, Lukas Bokelmann and his colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology analysed bone powder from the base of each of the skulls.

They used a preparation method that reduces modern contamination before sequencing, to isolate the Neanderthal DNA.

Filthy Monkey Men editor agrees

Asst. Professor of Anthropology at the Univ. of Liverpool, and a friend of this website, Adam Benton remarks:

Asst. Professor of Anthropology at the Univ. of Liverpool, and a friend of this website, Adam Benton remarks:

These Gibraltar Neanderthals were preserved in hot conditions and then played around with by scientists for nearly 200 years. Despite all of this being unfavourable for DNA survival, new techniques have managed to get some out of the skulls after all!

Note – Benton’s website, reporting on the latest finds in paleontology, is Filthy Monkey Men.

Chris Stringer – “Holds promise for the recovery of… ancient DNA from regions such as North Africa…”

Christopher Stringer, National Museum of London director and a favorite of this website is quoted in geneticliteracyreport.com, July 19:

Stringer adds, ‘These results show that it’s now possible to analyse DNA in highly contaminated fossils from relatively warm climates.

‘It holds out promise for the recovery of comparably ancient DNA from regions such as North Africa, the Middle East and China.’

On a side note, Sci Fi author Alan Felyk remarks:

I’m always elated to see real-life science catch up with one of my sci-fi ideas. In Damaged Beyond All Recognition, I write about Neanderthal children from Gibraltar who are resurrected from their ancient DNA. Looks like science has taken the first step.

The new process for ancient DNA extraction could have enormous implications for finally resolving modern Sub-Saharan African lineage. Homo naledia as Dr. Lee Berger has suggested, Homo Heidelbergensis or some other small-brained, primitive ghost species.

UPDATE!

Methods for DNA extraction are improving greatly. They now include extraction of DNA from soil samples.

Excerpt from InsideScience.org, 2021,

Neanderthal DNA Unearthed from Dirt

Roughly 100,000 years ago, a community of Neanderthals settled into a region of what we know as northern Spain, calling it home for many generations. The expansive limestone caves served as shelter from the elements, a workshop for making stone tools, and a kitchen for butchering animals.

Despite the rich history and activity at this site, known as Galería de las Estatuas, only a single Neanderthal fossil has ever been recovered: a pinky toe bone, too tiny to extract genetic material from without destroying it completely. Finding Neanderthal skeletal remains in general is very rare…

Additionally (Twitter):

“You can imagine a Neanderthal woman sitting in the cave, butchering a deer, and she cuts herself. She bleeds on the floor a little bit, and that blood has DNA in it, which binds to the dirt in the floor,” said Vernot. “Time passes, more dirt accumulates, and her DNA is trapped in the dirt. We can now go find it and learn about that person.”

UPDATE!

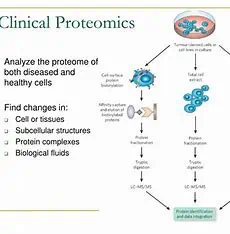

On the Hobbits – Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, Stringer is quoted in The Guardian:

“These are all really intriguing species and we only have a poor fix on how they relate to us,” said Stringer. “So proteomics could certainly help there.”