Out of Africa is losing adherents

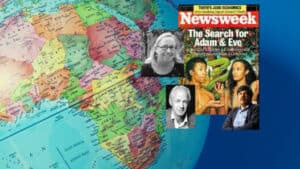

A seismic shift is underway in paleoanthropology. For decades, the “Out of Africa” model reigned supreme — a tidy narrative proposing that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa and dispersed globally around 45,000 to 50,000 years ago, replacing archaic hominins with little to no interbreeding. But that narrative is unraveling, and in its place, a more complex, Eurasia-inclusive model is emerging.

A seismic shift is underway in paleoanthropology. For decades, the “Out of Africa” model reigned supreme — a tidy narrative proposing that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa and dispersed globally around 45,000 to 50,000 years ago, replacing archaic hominins with little to no interbreeding. But that narrative is unraveling, and in its place, a more complex, Eurasia-inclusive model is emerging.

In this episode, we trace the quiet collapse of the classic model through two major developments: the public pivot of Chris Stringer, long considered the godfather of paleoanthropology, and the stunning implications of the Yunxian crania from China.

Chris Stringer’s Paradigm Shift

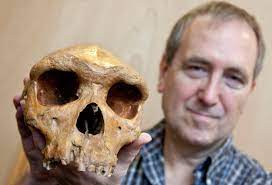

Professor Chris Stringer of the London Natural History Museum has been a towering figure in human origins research. Decorated by the Royal Society and honored with the Huxley Medal in 2023, Stringer was once one of the most passionate proponents of the Out of Africa model. But to his credit, he began expressing doubts as early as the 2010s.

Professor Chris Stringer of the London Natural History Museum has been a towering figure in human origins research. Decorated by the Royal Society and honored with the Huxley Medal in 2023, Stringer was once one of the most passionate proponents of the Out of Africa model. But to his credit, he began expressing doubts as early as the 2010s.

In a 2023 interview with Edge.org, Stringer reflected on his evolving stance:

“Twenty years ago, I would have argued that our species evolved in one place, maybe in East Africa or South Africa… Now, I don’t think it was that simple. Either within or outside of Africa, we end up with quite a complex story.”

Stringer’s shift isn’t just philosophical — it’s grounded in a series of discoveries that challenge the simplicity of a single-origin model.

Fossil Evidence and Genetic Ghosts

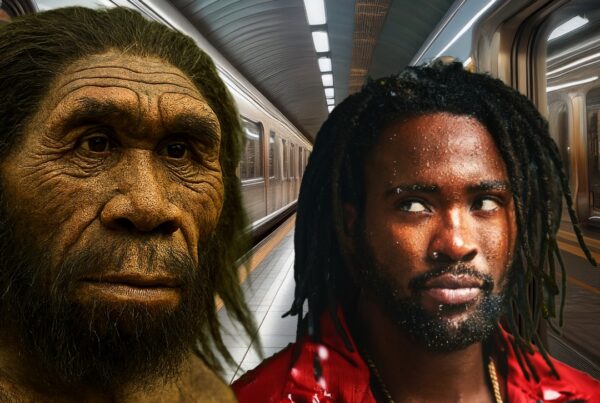

The 2010 discovery of Neanderthal DNA in the Eurasian genome by Svante Pääbo and his team in Leipzig was a turning point. It proved that interbreeding occurred — and that modern humans carry archaic genetic signatures.

The 2010 discovery of Neanderthal DNA in the Eurasian genome by Svante Pääbo and his team in Leipzig was a turning point. It proved that interbreeding occurred — and that modern humans carry archaic genetic signatures.

Then came the Apidima 1 skull cap from Greece. Reanalyzed in 2019 by Stringer’s colleague Katerina Harvati, the fossil was confirmed to be Homo sapiens and redated to 210,000 years ago. That places modern humans in Europe nearly 120,000 years before the Out of Africa timeline allows.

Meanwhile, geneticists at UCLA uncovered traces of a mysterious hominin lineage in modern Africans — one that diverged before Neanderthals. Their study revealed up to 19% archaic DNA admixture in African populations. As Stringer noted in The Guardian, “Africa had its own ghosts, just like Eurasia.”

The Yunxian Crania and the Eurasian Corridor Model

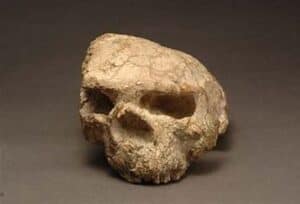

The recent reanalysis of the Yunxian skulls from China has further shifted the landscape. These fossils suggest a deep and continuous hominin presence in East Asia — one that complicates the idea of a late, singular migration from Africa.

The recent reanalysis of the Yunxian skulls from China has further shifted the landscape. These fossils suggest a deep and continuous hominin presence in East Asia — one that complicates the idea of a late, singular migration from Africa.

As fossil evidence and genetic signals converge, the Eurasian Corridor Model gains traction. This framework posits that human evolution was not confined to Africa but unfolded across a broader geographic canvas — from the Levant to Central Asia and beyond.

A Cinematic Breakdown of the Paradigm in Motion

This video presents a forensic editorial breakdown of the shifting paradigm. Through archival footage, layered narration, and cinematic pacing, we explore how the Eurasian Corridor Model is no longer fringe — it’s a serious contender.

We examine the ideological rigidity that once framed alternatives as fringe, and we celebrate the scientists who’ve dared to revise their own positions in light of new evidence. From Stringer’s quiet reversal to the ghosts in African genomes, the story of human origins is becoming richer, stranger, and more distributed than ever before.

Conclusion: Mostly, But Not Absolutely

Stringer’s words echo the new consensus: our evolutionary story is “mostly, but not absolutely” a recent African origin. That qualifier — not absolutely — opens the door to a more nuanced, multi-regional narrative.

The Out of Africa model may not be dead, but it’s no longer the sole framework. In its place, a mosaic emerges — one that spans continents, timelines, and genetic legacies.