Ghost Admixture, “Species X” in African Genomes

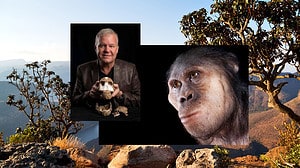

Superstar paleoanthropologist Dr. Lee Berger of Witwatersrand University in South Africa, first coined the term “Species X” in a series of interviews in 2019/20: “if it’s Species X for example, you know the missing species in the DNA of some African humans… I think there’s a real chance of it by the way…”

Superstar paleoanthropologist Dr. Lee Berger of Witwatersrand University in South Africa, first coined the term “Species X” in a series of interviews in 2019/20: “if it’s Species X for example, you know the missing species in the DNA of some African humans… I think there’s a real chance of it by the way…”

He was referring to Homo naledi. But as Berger noted early on after Naledi’s discovery in 2014, he initially believed H-Naledi was an Australopithecine. This view was echoed by other paleoanthropologists who remarked that Berger and his team had just discovered another Australopithecine.

In 2019, geneticists Sriram Sankararaman and Arun Durvasula identified a mysterious “ghost admixture” in African genomes (Paper). By 2020, Sankararaman explained to The Guardian: “They seem to have made a pretty substantial impact on the genomes of the present-day individuals we studied. They account for 2% to 19% of their genetic ancestry.” (The Guardian, Feb. 2020).

This was the birth of Species X — a lineage that left a genetic echo in modern Africans but had no clear fossil anchor.

The Ishango Tooth (~300,000 Years Ago)

Shara Bailey’s 2014 PLOS ONE paper on the Ishango tooth in the Democratic Republic of Congo provides a tantalizing clue (PLOS ONE, 2014). The specimen, dated to ~300,000 years ago, was a molar whose crown size, enamel thickness, and cusp morphology fit neatly within the range of Australopithecines. In comparative terms, the size and shape align more closely with Australopithecus africanus than with A. afarensis, echoing traits seen in Sterkfontein specimens such as Sts 5 (“Mrs. Ples”).

Shara Bailey’s 2014 PLOS ONE paper on the Ishango tooth in the Democratic Republic of Congo provides a tantalizing clue (PLOS ONE, 2014). The specimen, dated to ~300,000 years ago, was a molar whose crown size, enamel thickness, and cusp morphology fit neatly within the range of Australopithecines. In comparative terms, the size and shape align more closely with Australopithecus africanus than with A. afarensis, echoing traits seen in Sterkfontein specimens such as Sts 5 (“Mrs. Ples”).

This reinforces the interpretation that the Ishango tooth represents a late‑surviving Australopithecine, overlapping with early Homo sapiens in Africa. The parsimonious interpretation held by most paleoanthropologists is that the first putative archaic Homo sapiens emerged between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago, with Jebel Irhoud in Morocco as a leading candidate.

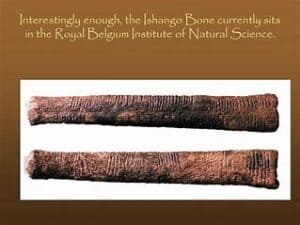

Note – Ishango is best known as the site where the magnificent Ishango bone was discovered, dated 13,000 years ago. The fossil is said to represent one of the first pieces of evidence in mathematical reasoning by our species.

Berger’s 2020 Tooth Discovery

In 2020, Lee Berger announced another astonishing find in South Africa: an Australopithecus tooth discovered in breccia. “It’s another big tooth individual… we don’t know what it is. We kind of know what it’s not right now… it’s not Sediba… not Homo naledi. Other than that we don’t know what species we’re dealing with other than a large tooth hominid. Very exciting though,” Berger explained.

In 2020, Lee Berger announced another astonishing find in South Africa: an Australopithecus tooth discovered in breccia. “It’s another big tooth individual… we don’t know what it is. We kind of know what it’s not right now… it’s not Sediba… not Homo naledi. Other than that we don’t know what species we’re dealing with other than a large tooth hominid. Very exciting though,” Berger explained.

His assistant Justin Zandile, live at the site, described the specimen: “This one is so big. It looks like a Robustus.” (YouTube: Update 3 from the U.W. 105 Expedition).

The discovery highlights the ongoing uncertainty in classifying late‑surviving Australopithecine fossils, reinforcing the possibility that ghost admixture in African genomes may stem from such enigmatic lineages.

What Is Australopithecus sediba?

According to the Smithsonian Human Origins Program, Australopithecus sediba lived in southern Africa between 1.977 and 1.98 million years ago. Discovered in 2008 at Malapa Cave, the fossils are unusually complete, showing entire skeletons near the time when Homo evolved. Details of the teeth, the long arms, and the narrow upper chest resemble earlier Australopithecus, while other traits — such as aspects of the pelvis, broad lower chest, and certain dental features — resemble early Homo.

According to the Smithsonian Human Origins Program, Australopithecus sediba lived in southern Africa between 1.977 and 1.98 million years ago. Discovered in 2008 at Malapa Cave, the fossils are unusually complete, showing entire skeletons near the time when Homo evolved. Details of the teeth, the long arms, and the narrow upper chest resemble earlier Australopithecus, while other traits — such as aspects of the pelvis, broad lower chest, and certain dental features — resemble early Homo.

This mosaic of primitive and derived traits has led many scientists to view Sediba as a possible transitional species, offering crucial insights into the origins of our genus.

Sediba as a Descendant of Africanus

Many paleoanthropologists see Sediba as a late‑surviving descendant of A. africanus. Lee Berger (2010, discovery paper): When Sediba was first described from Malapa (~1.98 mya), Berger emphasized its mosaic traits — some resembling Australopithecus africanus (narrow upper chest, long arms, primitive pelvis) and others resembling early Homo (broad lower chest, dental traits). This led him to propose Sediba as a transitional form, potentially descended from A. africanus.

Many paleoanthropologists see Sediba as a late‑surviving descendant of A. africanus. Lee Berger (2010, discovery paper): When Sediba was first described from Malapa (~1.98 mya), Berger emphasized its mosaic traits — some resembling Australopithecus africanus (narrow upper chest, long arms, primitive pelvis) and others resembling early Homo (broad lower chest, dental traits). This led him to propose Sediba as a transitional form, potentially descended from A. africanus.

John Hawks (UW–Madison) has echoed this view in his lab materials and public commentary, noting that Sediba’s cranial morphology (MH1) is often compared directly to Sts 5 (Mrs. Ples, A. africanus) from Sterkfontein. The comparison highlights continuity, suggesting Sediba could represent a derived branch of Africanus.

STw‑5 and Stringer’s Commentary

A paper on STw‑5 (“Mrs. Ples”), published in 2022 and now actively discussed by Chris Stringer, has reignited debate over Australopithecus survival (Nature, 2022). The re‑dating places the Sterkfontein fossils at ~3.4–3.6 million years, far older than the traditional 2–2.5 mya estimates, while clarifying their affinities with Australopithecus africanus.

A paper on STw‑5 (“Mrs. Ples”), published in 2022 and now actively discussed by Chris Stringer, has reignited debate over Australopithecus survival (Nature, 2022). The re‑dating places the Sterkfontein fossils at ~3.4–3.6 million years, far older than the traditional 2–2.5 mya estimates, while clarifying their affinities with Australopithecus africanus.

Stringer has emphasized how fluid the boundaries remain between Australopithecus and early Homo, underscoring that fossils like STw‑5 continue to reshape our understanding of lineage persistence.

Conclusion: Species X as Australopithecus

Taken together with Shara Bailey’s Ishango tooth (~300kya) and Berger’s reluctance to assign a firm extinction date to Australopithecus sediba, the forensic trail converges: Australopithecus lineages may have survived far later than mainstream narratives allow.

Many paleoanthropologists see Sediba as a late‑surviving descendant of A. africanus, and this makes Sediba itself a very likely contender for the “Species X” admixture identified by Sankararaman and Durvasula. What was once dismissed as a ghost lineage now appears to be a tangible echo of Australopithecus in modern African genomes.